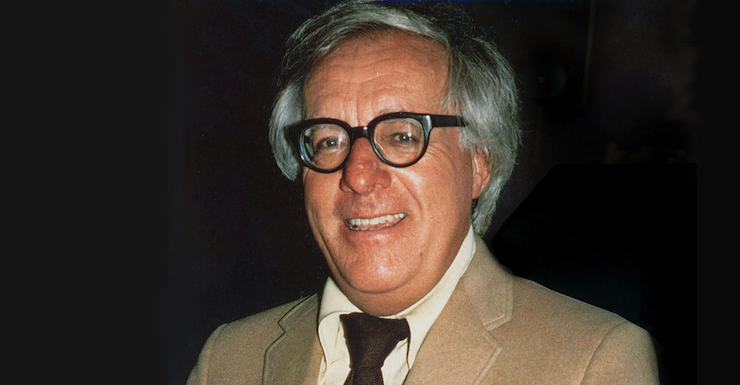

If you’re here on Tor.com, you’ve probably read some of Bradbury’s work. Scratch that. If you’re breathing and attended school in the last 50 years you’ve probably read some of Bradbury’s work. But, as most of us can attest, a classroom setting isn’t always the best place to truly connect with literature. Sometimes being “taught” a book, poem, or story, can strip it of its soul. Perhaps you did fall in love with Bradbury’s words when you first met, but then puberty and college and jobs, and the Mad Men marathon you did that one weekend, all got in the way. Well, it’s about time you reconnected with some of the world’s finest storytelling—not just in science fiction, but across all genres.

My first introduction to Ray Bradbury’s work did indeed come in a classroom, though not through the curriculum staple Fahrenheit 451. Instead, I met Bradbury in “There Will Come Soft Rains,” assigned by a desperate substitute teacher attempting to keep my 7th grade English class from spiraling into Lord of the Flies-like chaos. The story enthralled me: the quiet horror, the subtle way the mystery unfolds, the image of tiny robot mice with “pink electric eyes”—it was like nothing I’d ever encountered and I wanted more. Not long after, my dad brought home a copy of The Martian Chronicles for me to read. When I devoured that (probably in a single evening), he tried to satiate me with a huge collection of Bradbury’s short stories. I consumed it with a single-minded voraciousness that only kids seem to possess.

My dad (also an avid reader) was probably just grateful that I hadn’t descended into the wilds of a certain Sweet Valley popular at the time, but having a Bradbury enabler made all the difference to me as a reader. It even shaped who I would become as an adult, an idea that Bradbury himself touched on in his foreword for The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2012: “Think of everything you have ever read, everything you have ever learned from holding a book in your hands and how that knowledge shaped you and made you who you are today.”

So today, I hope to be a Bradbury enabler too. Though it’s difficult to pick favorites from the hundreds of stories he wrote, I think these five offer an excellent entry point. If you’re already a fan of Bradbury’s short fiction, I hope (re)reading these will inspire you to share a few of the stories that helped shape you in the comments below.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” (1950) available in The Martian Chronicles

“At ten o’clock the house began to die.”

The title comes from a Sara Teasdale poem of the same name, which is featured within the story itself. The poem and the story contemplate life after mankind has perished. In the story, Bradbury’s house of the future carries on with its daily tasks and machinations, ignorant that its human inhabitants are missing. Burned into this story, like the silhouettes on the side of the house, is the emotional aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It deftly reflects how the advent of atomic bombs would leave warfare and humanity forever altered.

“The Fog Horn” (1951) available in The Golden Apples of the Sun

“The Fog Horn blew.

And the monster answered.”

A seasoned lighthouse keeper “onboards” the new guy, attempting to prepare him for some of the job’s more unique “challenges.” It does not go well. As much about broken hearts, longing, and loneliness, as it is about sea monsters, “The Fog Horn” explores the collision of the modern world with ancient instinct. “The Fog Horn” was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post as “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,” and was the basis for a film of the same name.

“The Night” (1946) available in The Stories of Ray Bradbury

“Here and now, down there in that pit of jungled blackness is suddenly all the evil you will ever know. Evil you will never understand.”

Bradbury often drew inspiration from poetry, which is evident throughout his work. But for me, the poetry inherent in his prose is particularly vibrant in “The Night,” which includes one of my favorite sentences in all literature: “The town is so quiet and far off, you can only hear the crickets sounding in the spaces beyond the hot indigo trees that hold back the stars.” In “The Night,” Bradbury puts the reader in the shoes of a young boy, confronting true fear for the first time in his life. It’s more than concern for his missing brother, or being afraid of the dark as he and his mother search for him—it’s the deep bottomless fear of realizing one’s own mortality, and the vast loneliness that accompanies that realization.

“I Sing the Body Electric” (1969) available in I Sing the Body Electric and Other Stories

“Clever beyond clever, human beyond human, warm beyond warm, love beyond love…”

Initially published as “The Beautiful One is Here,” “I Sing the Body Electric!” draws its title from a Walt Whitman poem that examines the connection between the human body and the soul. In the story, a trio of siblings, grieving the recent loss of their mother, builds the perfect robotic grandmother to care for them. “I Sing the Body Electric” was originally a teleplay written by Bradbury for the 100th episode of The Twilight Zone in 1962. It was his only script to be produced for the show.

“The Lake” (1944) available in The October Country

“Water is like a magician. Sawing you in half.”

Like a lake, there’s more to this story than initially meets the eye. On the surface, it is a classic ghost story—a young man, revisiting the scene of a tragic accident makes an unexpected discovery. But beneath that, like so many of Bradbury’s stories, it is about teetering on the edge of childhood—moments from falling, leaping, or flying, into the unknown abyss of adult life. “The Lake” was also adapted into an episode of “The Ray Bradbury Theater.”

Originally published in June 2013.

When Nancy Lambert doesn’t have her nose buried in a book, she’s busy writing, cutting down restless draugrs in Skyrim, or putzing around online.